The Gray Whale Barnacle

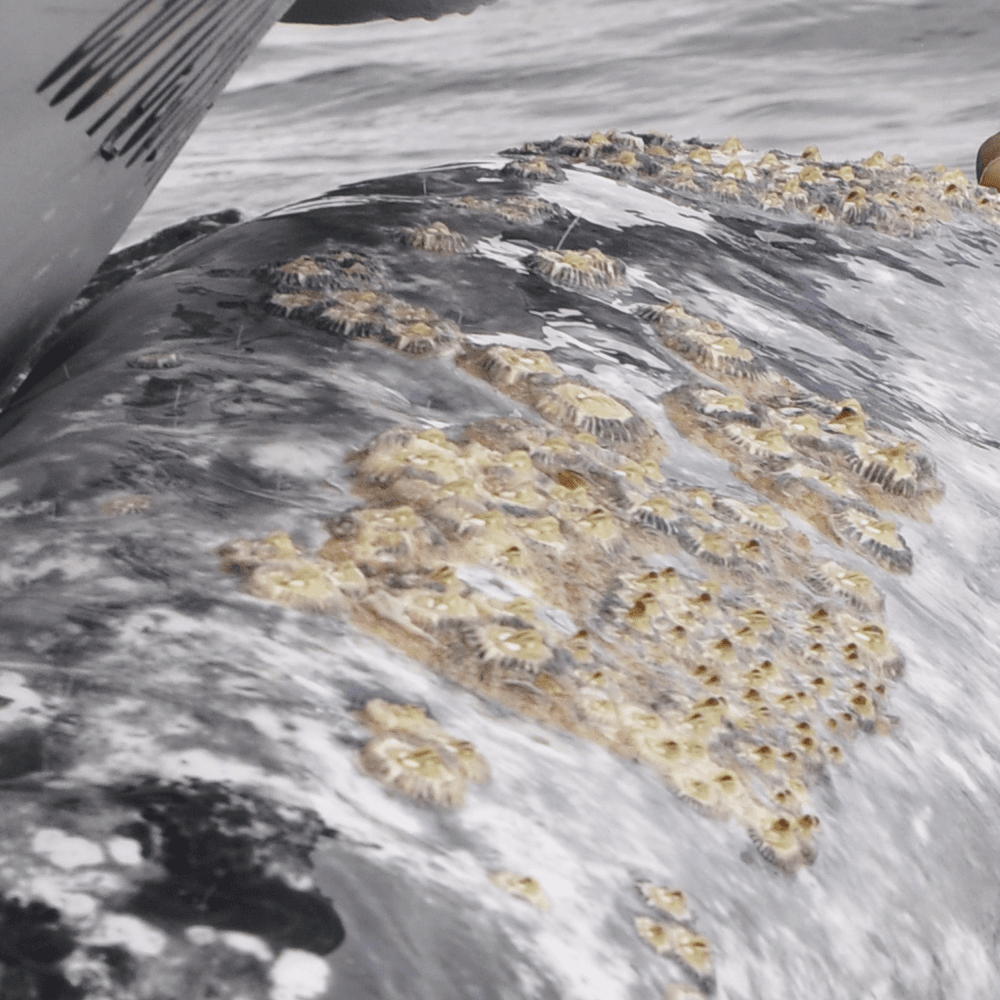

Barnacles are the most visually noticeable “parasite” that live upon the Gray Whales.

Here’s the taxonomy of the Gray Whale barnacle.

Cryptolepas rhachianecti = scientific name

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: Crustacea

Class: Maxillopoda

Subclass: Thecostraca

Infraclass: Cirripedia

Order:

Family:

Genus: Cryptolepas

Species: rhachianecti

Barnacles are obligate cross-fertilizing hermaphrodites. They can mate with any nearby barnacle. Inside the barnacle shell is a relatively long tubular penis 4” to 8” long. When ready to mate the barnacle protrudes this tube outside the shell and begins to search the nearby vicinity for a receptive fellow barnacle. The tube is then inserted into that receptor barnacle and sperm is deposited, thus fertilizing a portion of as many as 10,000 eggs. The temporarily female barnacle must be fertilized several times, perhaps by several “male” barnacles at different times in order for all of the eggs to be fertilized.

The eggs are brooded inside the mantle of the barnacle for a short period of time. Brooding varies among barnacle species and can be up to several months duration. But we know that small barnacles are visible upon whales within days or weeks of their arrival in the lagoons. Thus the conclusion is that these whale barnacles have a brief egg brooding period.

The eggs develop into a form called nauplius or nauplius larvae. These naupli are released into the ocean where they are free swimmers and become part of the planktonic soup.

These small crustaceans (yes, barnacles are closely related to creatures like shrimp and lobsters) have developed a life cycle that is closely tied to the Gray Whale migration. The barnacles have also adapted physically to their mobile environment. Instead of a tall rough shell like the stationary, upright, drag causing barnacles that grow on ships and rocks, the Whale barnacles have adapted to have a sleek and streamlined form, thus immensely reducing the drag they cause.

Writers and researchers generally say

that whale barnacles get a free ride to food and this is the number

one benefit they derive from life on board their whale associate.

I rank delivery to a food source as the secondary benefit, not the

primary benefit for the barnacles.

There is a much more obvious benefit that the barnacle species derives

from living upon the back of the whale, one that is commonly overlooked

in discussions about whale barnacles. This is the security that being

mobile provides to the barnacle. Living upon the back of a Gray Whale

means they are free from attacks by the most common enemies of the

various barnacle species.

Stationary barnacles are regularly attacked and eaten by sea stars

(starfish), sea cucumbers, some sea worms, as well as various snails

and whelks. Small fish find it easy to hover over barnacles and nibble

at the animal as it extends itself from the protective shell to feed

upon passing plankton. Larger, heavily toothed fish, such as Sheepshead,

can actually crunch the tough limestone shell to get to the barnacle

inside.

Living upon the back (or bottom) of a gray whale the barnacles never need to worry about any of the common invertebrates that prey upon the stationary forms of barnacle. Some small fish in search of food do follow the Gray Whales when they are in the Baja Lagoons. These small fish eat food that is stirred up by the gray whales from the shallow bottom of the lagoons. These small fish also prey upon whale lice and very occasionally upon barnacles.

The photo to the left is a close up of a single whale barnacle, open and feeding. The scale is about 2 to 4 times life size.

The living barnacle is the light yellow colored membrane, with

the open cirria or filter membrane showing inside.

There are three large (about 1/2 “ to 1” long) whale

lice in the space between the barnacle and the barnacle shell.

The darker gray color is the barnacle shell.

Photo – copyright 2008, Keith Jones Equipment: Nikon D70 with 200 mm Nikor macro close up lens, handheld and using natural lighting in a live situation.